Publishing events from a web application is possible with NServiceBus, but it should be carefully considered before implementation. This article will describe the guidelines for publishing messages from within web applications under different circumstances.

Firstly, there are good reasons to avoid publishing events from within web applications:

- Transactions and consistency - Events should announce that something has already happened. Many times, this involves making changes to a database and then publishing the result. However, HTTP is inherently unreliable and does not have built-in retries. If an exception occurs before the event is published, the only opportunity to publish that event may be lost. In these circumstances, it's generally better to send a command with the payload of the HTTP request and have another endpoint process the command. Doing this takes advantage of NServiceBus's recoverability capabilities.

- Resource optimization - The most precious resource in a web server is a request processing thread. When these are exhausted, the server can no longer handle additional load and must be scaled out. Complex database updates (possibly involving the Distributed Transaction Coordinator) can block these request threads while waiting for I/O to and from the database. In these situations, sending a command to a back-end processor is more efficient. Typically this allows for better scalability with fewer server resources.

- Web application scale-out - Because events can only be published from one logical publisher, it can be problematic to scale out a web application publishing events. More on this below.

Given these facts, conventional wisdom suggests that in a web application, it is better to only send commands to a back-end service endpoint, which can then publish a similar event.

But this is not always the case. Not all transports handle publish/subscribe mechanics in the same way - many support it natively. Also, cloud transports generally have an associated cost per interaction; sending a message unnecessarily before publishing costs money.

Publish/subscribe mechanics

It's important to understand how publish/subscribe operates, consisting of the subscription phase, followed by the publish operation.

Subscription

An endpoint must register its interest in a message by subscribing to a specific message type. The mechanics for how this occurs depends on the message transport being used.

Many transports (e.g. Azure Service Bus and RabbitMQ) support publish/subscribe natively; when an endpoint wants to subscribe to an event, it contacts the broker directly and the broker keeps track of subscribers for each event.

For transports that lack native pub/sub capabilities (e.g. MSMQ, and Azure Storage Queues) NServiceBus provides similar semantics by using storage-driven publishing with message-driven subscriptions. This means that each endpoint is responsible for maintaining its own subscription storage, usually in a database. When an endpoint wants to subscribe to an event, it sends a subscription request message to the owner endpoint, which will update its own subscription storage.

Publishing

The publishing process also differs based on the message transport.

A transport that supports native pub/sub will send the event message directly to the broker, which will distribute the message to all registered subscribers.

A transport that uses storage-driven publishing will act differently. When it needs to publish, it will consult its subscription storage to determine the interested parties. It will then send an independent copy of the event message to each subscriber.

While it is common to think of an event being published from a specific location, this doesn't always reflect the reality of the messaging mechanics. For native pub/sub brokers, there is no from concept. Instead, they publish an event, and the broker figures out the rest.

In the case of storage-driven transports, however, the "publish from" location actually relates to the input queue that is set up to receive subscription requests and store them in the subscription storage database.

Load balancing

Typically, web applications will be scaled out with a network load balancer either to handle large amounts of traffic, or for high availability, or both. In elastic cloud scenarios, additional instances of a web role can be provisioned and later removed, either manually or automatically, to keep up with changing load. In either case, this constitutes multiple physical processes that could potentially publish an event.

An important distinction of an event is that it is published from a single logical sender and processed by one or more logical receivers. It's important not to confuse this with the physical deployment of code to multiple processes. In the case of a scaled-out web application, the individual web application instances are physical deployments; all of these together can act as a single logical publisher of events.

In order to make this work for storage-driven transports, such as MSMQ and Azure Storage Queues, the nature of publishing means that all physical endpoints must share the same subscription storage. Normally one centralized subscription storage database is used for an entire system, so this isn't a difficult requirement to meet.

Although this speaks specifically to web applications, it's worth noting that the same applies to scaled-out service endpoints.

Storage-driven transport topology

For storage-driven transports, it is not recommended to have one of the web applications receive subscription requests. Instead, each web application instance can be implemented as a send-only endpoint, and a back-end service endpoint can be responsible for receiving the subscription request messages and updating the subscription storage.

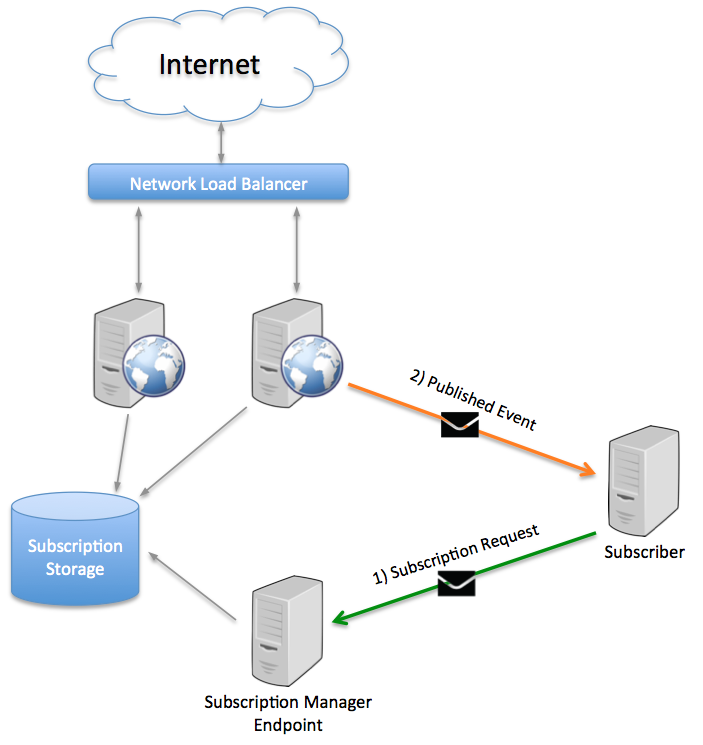

In the diagram above, two web servers are load-balanced behind a network load balancer. The applications on both web servers cooperate by referring to the same subscription storage database.

An additional Subscription Manager Endpoint exists off to the side, also talking to the same subscription storage. When a subscriber is interested in an event, the subscription request message is routed here, not to either of the web servers. When a web server needs to publish an event, it looks up the event type in the subscription storage database and publishes it to the subscriber.

The subscription manager endpoint can be any endpoint identified to process the subscription requests as long as it uses the same subscription storage as the web servers. The subscription manager endpoint can process other message types as well.

In this way, the web servers, together with the subscription manager endpoint, work in concert as one logical endpoint for publishing messages.

If the web applications need to also process messages from an input queue (for example, to receive notifications to drop cache entries), then a full endpoint (with input queue) can be used, but none of the web servers will ever be used as the subscription endpoint for the events published by the web tier.

In an elastic scale scenario, it's important for endpoints to unsubscribe themselves from events they receive when they shut down. Otherwise, once decommissioned, they may leave behind queues that would overflow, since there would no longer be an endpoint to process the messages.

Summary

It can be useful to publish events from a web application. Always keep the following guidelines in mind:

- Don't publish from the web tier if an exception occurs before the event is published, as this could lead to data loss.

- For storage-driven transports, all web application instances must share the same subscription storage.

- Never use an individual web server name to identify the source of an event being published, which would interfere with effective scale-out.